Race, Equity and Housing: NAHRO’s Response

In Part One of this series, we explored the far-reaching and damaging policies like redlining that have paved the way for racially explicit housing segregation and argued that many of those policies were born in public housing. This article moves us forward and articulates a set of policy actions that the NAHRO Board of Governors has adopted to begin to redress those inequities. This article begins with a very brief summary of the key concepts. You can find the full article here.

Executive Summary of Race, Equity and Housing

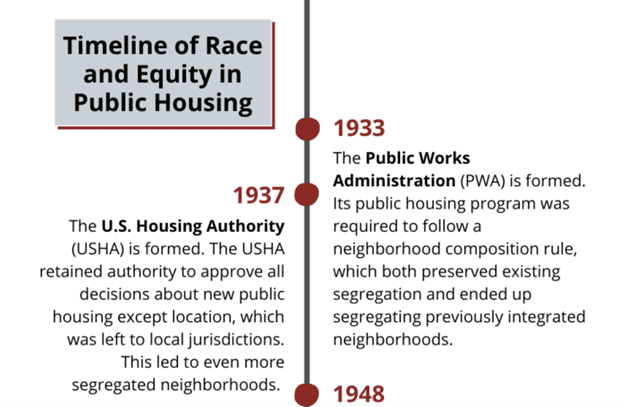

The housing sector has been a significant contributor to institutional and legislated patterns of racial and economic segregation, injustice and inequity[1]. The U.S. system of intentional housing and residential segregation began with public housing, the U.S. Housing Authority and its predecessor the Public Works Administration (PWA)[2]. Public housing frequently created segregation where it previously hadn’t existed, dismantling integrated neighborhoods and relocating people of color to neighborhoods that lacked access to jobs and transportation. The lack of access to capital and opportunity as a result of racially influenced homeownership policy has given rise to gaps in wealth, education, health and opportunity that people of color, and specifically African Americans, have never recovered from.

“This is no time to engage in … the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.”

Equity in Action: Where Do We Go from Here?

Following a year of study and consideration by NAHRO’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisory Committee, NAHRO’s Board of Governors adopted the Equity Policy Framework as presented. This framework provides a path forward for leaders who are ready to translate thought into action and aspiration into program. It is an invitation, not a mandate. Don’t let the word framework trip you up; think of this as a toolbox with the availability of many tools. Not every tool is meant to be used for what we are collectively building, but we guarantee there is something for you – something that will help you, in your area, deliver better services, better understand your residents and better partner with your community.

It is an invitation, not a mandate. You are invited, through this framework, to consider what you can do with your policy, programs, influence and community partners to create a more inclusive and equitable America.

The framework consists of six policy focus areas and 16 program categories.

HOUSING

We are focusing on housing choice. When federal funding and the national narrative shifted from public housing production to housing vouchers, the program became about choice. When HUD offered a deconcentration bonus, that was also about choice. An intentional, and sometimes unintentional, thread running through housing policy is a desire for our program and housing recipients to have a broader variety of neighborhoods in our communities to call home.

Additionally we are focusing on our technical deliverables and ways to increase education, advocacy, and conversations around the “math” of our voucher calculations. Our policy framework encourages our members to continue to request assessments and rule changes that increase housing options, allow for broader income inclusion, and allow for the different housing types – traditionally through zoning, code, and planning- that allow for robust housing options.

Today only one in four families and households that need, and are eligible for, rental housing assistance are able to access it. Rather than a ‘luck and lottery’ approach to something as vital as quality, stable affordable housing, we call on all levels of government to adopt a universal standard for voucher access.

Too many families with a housing voucher can’t use it because landlords have a negative perception of unearned income. Many local communities and states have begun to pass laws prohibiting landlords from rejecting a prospective renter based on income source. We call on more communities to follow suit.

Too many voucher families live in areas of highly concentrated poverty and low opportunity. Families could more easily move to opportunity if the issue of inadequate subsidy is solved by more widely implementing small area FMRs. We call on all PHAs to look at small area FMRs.

- Educate NAHRO members and provide technical assistance on the critical role zoning has played as an impediment to affordable housing expansion and racial equity.

The very earliest zoning laws were designed to create areas of exclusion rather than neighborhoods of inclusion. Large single family lots and low density zones are implicit, and explicit, barriers to housing affordability. These local laws can be changed by local action and we invite NAHRO members to consider taking the lead or joining the effort.

Fewer than one half of one percent of all voucher families are pursuing homeownership. The primary source of wealth creation, wealth accumulation and the onboarding to social mobility and upward mobility in the United States is through homeownership. Our policy framework advocates for this to continue at local, state, and national levels. We need to be intentionally inclusive of products that would help provide greater underwriting and support options to expand homeownership opportunities, especially for our families that participate in our family self-sufficiency programs and continue to use the opportunities presented to them to become mortgage ready.

PHAs can take a hard look at moving from a renting paradigm to an ownership model.

Historically, this nation has used the expansion of creative underwriting, investments in infrastructure, granting and discounting of buildable land, and zoning to improve homeownership rates. We know that focusing on this will help to provide the sustainable, inclusive, and stable communities our residents deserve.

Our country has experienced disproportionate effects from the recession across income brackets. Even high-earning Black homeowners were 80% more likely to lose their homes than their White counterparts. The financial crisis was sparked by a housing market collapse that had its roots in racial discrimination. It resulted in mass foreclosures that impacted racial minorities with disproportionate ferocity.

The after-effects of the Great Recession continue to deepen racial inequality. On top of equity/wealth lost due to the foreclosure crisis, house prices fell by 15.9% in 2008, the biggest annual drop since 1991, which resulted in further equity loss. That gap persists today. According to the Atlantic, by 2031, the downturn will have decreased the wealth of the median black household by almost $100,000.

- Provide 0% interest loans to low- and moderate-income families with a focus on families who have historically experienced low homeownership rates.

When the concept of home mortgages was created in the 1930s, African Americans were specifically excluded from purchasing homes in the newly expanding suburbs with the use of restrictive covenants. This explicit barrier to wealth acquisition, not to mention economic opportunity, can be remedied by advantaged borrowing today.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE

There is no greater visible inequity between racial and ethnic groups and classes than in the justice system. African Americans are more likely than white Americans to be arrested; once arrested, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, they are more likely to experience long prison sentences. A recent report to the United Nations provided a stark assessment: “The United States in effect operates two distinct criminal justice systems: one for wealthy people and another for poor people and people of color.”

We know that this is a difficult conversation in many communities because the narrative can be misconstrued. Our framework is clear. We have seen the effect of opioid and fentanyl addiction. We have seen the effect of lack of mental health counseling and health services and their compounding effect over time.

We also know that with smart and comprehensive administrative and screening changes we can help provide a safe living environment for those who have primarily been barred from accessing housing due to the effect of their addictions or the lack of health counseling access. The penalties continue even as they work toward making amends, getting the help they need, and staying stable on their path to healthiness.

NAHRO members can consider taking any of these actions to help re-balance the scales of justice.

- Limit the number of years criminal history can be used for housing decisions

- “Ban the box” – consider only violent felonies or drug manufacture and distribution felonies in housing admissions

- • Support and/or develop re-entry programs for incarcerated family members in concert with local providers.

SELF-SUFFICIENCY

When the United States created its first federal housing program in 1937 it was designed to create a bridge from public assistance to self-sufficiency. Over the years changes in legislation have created as many traps and cliffs as there are bridges. We can begin to change that by supporting investment strategies in small and micro-businesses and redirection of programs that create structures and systems to help protect and sustain our families, especially as they begin to benefit and improve financially. This includes extended disallowances for increased incomes and continuing to allow for asset building with a focus on improving homeownership, education financing (and reduction of the need for the debt, including in professional and technical degrees), and retirement accounts.

With a redirection and support of the overall financial infrastructure for our families- with a definition in support of their long-term sustainability and upward mobility in key areas- including supporting anti-poverty solutions and social safety net programs, our framework aims to continue to support our communities upward mobility.

- Gently reduce dependence on assistance by rewarding earned income. Too many housing programs penalize increased income, particularly with an increase in rent. Many MTW programs are experimenting with flat rents and other rent structures that reward, rather than discourage, increased family income.

- Workforce development programs are critical for families who have experienced years or decades at the economic and opportunity margins of society. The number of workers living in housing in low-wage jobs is a barrier to self-sufficiency.

EDUCATION

More than 750,000 children from birth to age eight are living in public housing in the United States. Research shows that 80% of children from low-income families enter kindergarten so far behind that they do not catch up and are unable to read proficiently by the end of third grade, a key predictor of high school graduation. Prior to third grade, children are learning to read; after third grade they are reading to learn. Grade-level proficiency is critical to future academic success.

School catchment areas don’t right-size the difference between the tax base and the funding needed for our children to get a quality education.

Some of our communities lack the excess capital to funnel additional resources to parent teacher associations or parent organizations because those financial resources don’t exist. This is why our commitment in our framework is bridging the gap in all our communities.

- PHAs and CDCs can improve internet/digital access in low income areas using either direct or partnered investment. Bringing school-based optic fiber to your community or including community and residential WiFi into all of your building plans are best practice standards.

- Universal access to preschool has been so demonstrably proven as an equity building strategy that many states have now adopted legislation to assure that all children have an educational headstart. PHAs and CDCs have many touchpoints with families where support for enrollment in preschool can be delivered.

- Under-resourced schools have an enormous impact on education gaps and upward mobility and the perpetuation of a property-tax funded school system exacerbates the problem. NAHRO members can join in advocating for equitable funding for neighborhood schools.

ACCESS TO RESOURCES

Last but not least, we call out the social infrastructure investment needed to improve the quality of life in neighborhoods, from physical improvements and investments like sidewalks, roads, and bridges, to improving the tree canopy, which has shown to reduce residents’ cost of heating in the winter and cooling in the summer. This level of specific economic development incentivization and digital upgrades will help make sure our communities continue to be great places to be.

Our ideas are spreading. Many policy theorists are beginning to see these very connections that we identify and the potential to use housing and neighborhoods as a platform for bringing resources closer to families. Access problems can include transportation and child care or language and cultural confidence. So many access challenges can be solved by co-locating services where NAHRO members are.

The framework calls out three resource needs: healthy food; dental access; and medical access

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Research has now proven that there are a set of factors that determine the health trajectory of a person’s life. These social determinants of health can create a resource and advocacy framework for organizations that focus on families. Recent events, and particularly the pandemic, have brought into very sharp relief the depth of equity imbalance and resource barriers in our society. Lower income families have experienced greater incidences of illness; lower-income children are experiencing chronic school absenteeism creating greater gaps in learning; lower-income men can expect to live, on average, 12 years less; experience much higher levels of stress; greater incidence of obesity;

This framework strongly encourages PHAs/CDCs to become access points for the Social Determinants of Health: economic stability, education, social and community context, health and healthcare, and neighborhood and built environment.

Where to from Here?

Since March 2021, when NAHRO’s Board of Governors adopted this Equity Framework, each of its strategies has been assigned to a committee of jurisdiction to map a strategic path forward. Many of the actions and ideas presented don’t require a change in policy or legislation. NAHRO members can pursue a host of strategies in their own community today.

NAHRO’s interactive database of Awards of Excellence and Merit can help put you in touch with colleagues that are already innovating with this framework. NAHRO conferences and webinars are also a great source of learning and sharing ideas and NAHRO’s professional development catalog is continually increasing the number of trainings on diversity, equity and inclusion strategies. We recommend three simple steps from here: educate yourself about what your organization and community needs in terms of closing opportunity gaps, innovate with your community partners and act. If not you, now, then who?

[1] Rothstein, Richard; The Color of Law….

[2] Rothstein

More Articles in this Issue

Bringing Equity and Inclusion into the Heart of NAHRO: the LGBTQ+ Subcommittee

Since its reformation in 2017, NAHRO’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisory Committee (DEIAC) has both…Beautifying Buildings and More: The Collaboration Between NiREACH and Eudora Baker

Eudora Baker (right) with one her many pieces of artwork. Eudora Baker is one of…Presenting the 2022 NAHRO Buyer’s Guide!

Each year, NAHRO publishes our Buyer’s Guide, a list of companies that work in the affordable…